The Wireless Man

His Work & Adventurers on Land & Sea

by Francis A. Collins, 1912

CHAPTER II

THE WIRELESS BOY

AN audience of a hundred thousand boys all over the United States may be addressed almost every evening by wireless telegraph. Beyond doubt this is the largest audience in the world. No football or baseball crowd, no convention or conference, compares with it in size, nor gives closer attention to the business in hand.

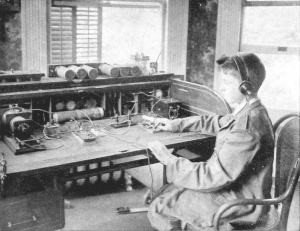

A simple but efficient amateur station. |

The skylines of every city in the country are festooned with the delicate antennae of the amateur wireless operators. They will be found skillfully adjusted to thousands of barns or haystacks in the most remote parts of the country. Let a message be flashed from some high-powered station anywhere between the two oceans and it will be skillfully picked up and read by thousands. The great station at Panama has been read simultaneously by boys at New York, in the Middle West and in California. On every fair night after dinner-time and when, let us hope, the lessons for the next day have been prepared, the entire country becomes a vast whispering gallery.

Not all of the amateur wireless operators, less than half in fact, are able to reply to the wireless messages which they pick up. It is safe to estimate, taking the entire country, that about forty per cent of all amateur stations are equipped both with receiving and sending apparatus. The rest merely "listen in" at thousands of wireless messages flashing above their heads. The average amateur station can send only over a short radius of about five miles, which is quite enough for neighborhood work. The more complete amateur stations send for about one hundred miles. The same stations can receive from stations one thousand miles away or even farther.

Over and over again it has happened that an exciting piece of news has been read by this great audience of wireless boys, long before the country has heard the news from the papers. The news of the loss of the Titanic was picked up by many boys along the Atlantic coast hours before the newspapers arrived. In several cases important C.Q.D. calls, telling that the lives of hundreds depended upon quick relief, have been missed by the great receiving stations, to be caught up by some alert amateur and sent to the office of the ship companies, thus saving many minutes of priceless time.

This great audience of boys, particularly those scattered along our seacoasts, help to make safe the lives of all those at sea. Through some accident or oversight the regular commercial receiving stations may fail to catch a distress signal. There are often scores of messages flashing through the air at the same time, and the great stations may be attuned to a certain ship and busily receiving when the more important signal passes. But the thousands of amateur wireless antennae sift out the messages of the air most thoroughly. It is extremely unlikely that a single call will pass over all these thousands of stations without being intercepted by many alert boys.

This unique wireless protection is enjoyed not only along the Atlantic seaboard but by the Great Lakes as well and along the Pacific coast. A C.Q.D. sent out from a vessel in distress on Lake Michigan, for instance, is usually read by scores of amateurs in and about Chicago. There have been several cases of such distress calls being first picked up by amateurs and sent in to the steamship officers before the powerful commercial stations had caught them. Scattered along the Pacific coast at Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles and other points are many enterprising wireless clubs representing thousands of amateur stations.

A wide-awake amateur often finds himself independent of such slow-going methods of spreading the news as newspapers or even bulletin-boards. During a particularly exciting baseball season recently an enterprising New York newspaper employed wireless electricity to flash the progress of the great league games from the ball park to the roof of the newspaper building. From a wireless station overlooking the diamond the progress of the game was sent move by move. The exact position of the men on the bases was then shown on a bulletin-board in the form of a diamond and an admiring crowd watched the game as it was played.

The sending apparatus at the ball field had a working radius of more than one hundred miles. The result was that all about New York the amateurs within a circle two hundred miles in diameter were extremely busy listening delightedly every afternoon to the very freshest possible news of the great games. It would be impossible to estimate just how many boys were thus informed of the score, inning by inning, but they were doubtless numbered by thousands. Firmly attached to their receiving sets they enjoyed all the excitement of the game in detail just a little earlier than the crowds which faced the bulletin-boards on Newspaper Row.

And later, when the football season arrived, the wireless boys about New York enjoyed another unexpected windfall. The rivalry was especially keen between the elevens of Columbia University and Princeton. The great game long anticipated was played at Princeton. For thousands of boys who were unable to attend the contest there would naturally be an agonizing interval of several hours after the game was decided before the latest editions of the newspapers would arrive.

Several enterprising amateur wireless men at Columbia, who were ,unable to make the trip with the team, arranged to receive the news from Princeton of the progress of the game at the wireless station atop one of the college buildings. The good news spread rapidly among the amateurs about New York. Hundreds of boys in New Jersey, Connecticut and New York made arrangements to receive these dispatches, and it proved to be a very happy afternoon for some hundreds of football rooters who had been obliged to stay at home. The messages were relayed by way of Atlantic City and Sea Gate.

"Game called," sang the wireless instruments, amid the suppressed excitement of this widely scattered football audience.

"First down ball on Princeton's forty-yard line," came a few minutes later.

Except for the fun of shouting in chorus with your friends there could be nothing more satisfactory. There followed nearly two hours of such reports and when the final score was announced the amateurs were thrilling with the news of victory before the actual football spectators had had time to overrun the field. An afternoon like that would alone repay any amount of trouble in installing one's wireless apparatus.

One of the most ambitious wireless experiments ever attempted in America was the intercollege chess tournament, played between the teams of four Eastern colleges recently. The moves were transmitted by the amateur operators from the wireless instruments of the various colleges. The usual practice of numbering the squares of the chess-boards and of indicating the moves by sending the numbers was followed. A number of games extending over several hours were thus played without confusion, although the chess teams were in some cases upwards of one hundred miles apart.

The receiving stations about New York for several years have been reading the messages sent out by a girl somewhere in the vicinity to a particular steamer. No one knows just where the young lady lives-it may be in Connecticut, New York, or New Jersey-but they look upon her as an old friend, and sympathize with her. She sends regularly from her home to a brother who is a wireless operator on a great transatlantic steamer. For two or three days after the brother's steamer leaves New York and again for many hours when the steamer is nearing port, there is the liveliest kind of an interchange of messages between the two.

Hundreds of operators, both amateur and professional, Dave listened to the home news and the gossip of the brother and sister. During two days or more while the steamer, outward bound, is skirting the coast to the north, the sister tells him of the health of the family, the callers and bits of family gossip. And just before the steamer gets out of range there is always an affectionate good-by from all at home. On the return trip as soon as the ship has reached the Banks the messages begin again. Welcomes are exchanged and questions are asked and answered about the entire family, including the dog.

"She is a nice girl," a New York amateur remarked to the writer. "Her sending is intelligent and clear cut, always. And when she is interrupted or some mannerless operator somewhere tells her to keep quiet, she never gets mad but apologizes very good naturedly." Perhaps the young lady may chance to read this page, whoever she may be, and learn with pleasure the good opinion the operators have of her.

To keep everything ship-shape and regular in their stations many amateur

wireless operators keep up a careful log of all messages received and

sent. On shipboard the wireless man as a rule writes down his log on large

sheets of paper ruled with a single vertical line about one inch from

the left side. In this column he sets down the exact time to the minute

a message goes out or is received and, opposite, a brief summary, giving

the stations in communication, the message, and whatever comment seems

necessary. Such a record is, of course, quite as important to the wireless

man as

bookkeeping to a merchant. In cases of dispute this log may prove of the

most vital importance.

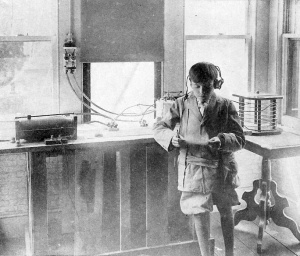

Listening in. |

Modeling his log along these lines the amateur often sets down his wireless conversations in a special book. Such a log soon becomes a valuable record. It preserves, for one thing, the wireless calls of the various steamers and stations. By referring to the log the amateur is able to tell in a moment who is sending. An operator who works industriously from his home in Montclair, New Jersey, has in this way collected more than one hundred and fifty different wireless calls or signals sent from as many stations, which he has picked up and read. There are, of course, many more sending stations heard in and about New York, but the amateur has done very well.

The greater number of these are picked up from ships at sea, entering or leaving New York harbor. It is a very simple matter to read the messages from the transatlantic liners as they turn northward after steaming out past Sandy Hook. The coast. wise steamers passing both up and down the coast are even more numerous. To these are added the warships, several of which are usually in the harbor or within calling distance. There are besides six large commercial stations in New York City. Several of the United States Army stations along the coast, with a sending radius of upwards of a hundred miles, especially the one at Sandy Hook, may also be read. From a page chosen at random from one of the amateur logs one may get some idea of the delights of an evening in an amateur wireless station.

SATURDAY EVENING

8 :10 - Sent out RQ. (this station's private call).

8 :12 - Answered by Herbert. Signals exchanged.

8 :14 - Picked up S.S. Baltic. Sending passen-

ger's message to Sea Gate, arranging

for hotel room.

8 :20 - Government station, Brooklyn Navy Yard,

drowns out everything - sending to

Washington. Cipher message.

8 :25 - Heard three local calls. Tuned to talk to

Harry. Got new bicycle, asked me to

come see it.

8 :28 _ Steamship, inward bound, reporting posi-

tion. Some freighter, didn't wait for name.

8 :37 - Overheard Bennet and Herbert talking

to each other. Chewing the rag over next

Saturday's baseball game.

8 :42 - Caught part of a message from Sea Gate

station to the Finland, going out. Pas-

senger business.

8 :48 - Got Walter's can, worked fine. Been to

New York to-day. Told me he has

new magneto that's a peach, can send

one hundred miles anyway. He went

to basebal1 game in afternoon. Matty

pitched and shut out the Pirates. Best

game he ever saw. Told me an about it.

9 :02 - Sending out wireless news for wireless

newspaper from Battery, New York, so

loud I can't tune to anything. Repeats

news in last edition of evening paper.

Nothing new till end. Latest news from

Chicago Convention, looks as if

Taft would be nominated to-night.

9:20-Awful rush of cans, breaks in when news-

paper shuts off. A lot of stations tel1-

ing each other to shut up and give them

a chance. Big commercial station on

lower Broadway sends, "You kids shut

up." Guess I'll stop for to-night.

Shut off.

One of the greatest pleasures of the amateur wireless man is the long-distance club meeting. The amateur clubs are usually small and the members live within easy wireless sending range of one another. Such a meeting can be held with upwards of twenty members, and the affairs carried on in a strictly parliamentary fashion. An hour for meeting, talking rather, is agreed upon, when each member tunes his instrument to talk with the other stations and stands by ready for the call which is to bring the meeting to order. It is usually found best to have all the members "attending" the meeting within a radius of about five miles, although meetings have been called with members much more widely separated.

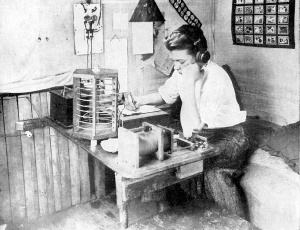

An Amateur "wireless man" at work. |

Promptly at the appointed hour, say eight 0' clock of an evening, the chairman calls the meeting together by sending out his code signal. The members reply briefly by sending their private signals, usually a single letter, which amounts to their rising in meeting and replying "present." The chairman picks these up one by one and sets them down in his log which now becomes the minutes of the meeting. To be sure something may go wrong with some apparatus in the group which forces a member to keep quiet and be marked absent, although he 'can listen to what is going on even if he does lose his vote.

"Meeting called to elect president," the chairman spells out. "All in favor say 'X.' "

"X -X -X-" the air is full of messages, while several members vary the call by sending, "Sure, go ahead." "We hear," etc.

"Contrary vote '2,' " spells out the chairman. The air is suddenly silent.

For the convenience of all concerned such meetings are usually cut and dried affairs as the saying goes. It is a packed convention.

"Who's nominated?" There is no need in wasting time to keep to parliamentary forms.

"Brown-Smith," crack a score of sending instruments. The chairman waits until order once more reigns in the atmosphere.

"Brown and Smith. Vote. Take your time," he announces, and prepares to count the votes. To save time each member in casting his vote sends the name of his choice in the election followed by his private signal.

"Brown Z," "Smith W," "Smith L," "Smith G," "Brown K." The votes fill the air to be picked up by the presiding officer. A pause follows while the chair is counting the ballots. The members wait impatiently.

"Brown, six; Smith, eleven," comes the result of the election. Every member gets the returns at the same instant, exactly as though they were gathered in the same room. There has been one exception, however. One of the members has had a slight accident to his instrument and the bulletin has come in while he was mending it. He asks for a repetition and gets it.

"Hurrah, three cheers for Smith I" spells out an enthusiastic friend. Several members, ignoring the chair, begin arguments between themselves and confusion reigns in the air, as it might in any political meeting. The chairman sends out his private call, which is equivalent to pounding with his gavel, until order is restored and the sending instruments are again silent.

. -- "President Smith will take the chair," he announces, and cuts off.

"Many thanks," the president-elect now sends. "Any motion to be presented?"

"X, Z, S, K, I, Y," come a dozen calls.

"X has the floor," announces the president.

And so the wireless meeting runs.

The clubs of amateur wireless operators are doing excellent work in developing

the science. There are hundreds of such organizations scattered over th<:;

length and breadth of the country which have regular meeting places or

special club-houses. Here the members gather regularly to discuss various

problems and. demonstrate new theories and inventions with the aid of

blackboards and practical apparatus. Some of the clubs are open to members

of twelve years and it is common for a club to limit its membership to

boys between say fourteen and eighteen years of age. In many of the larger

clubs amateurs are only admitted to membership after they have passed

a rigid examination, just as engineers or masters of vessels' apply for

licenses. Among this great army of amateurs will be found some of the

most expert operators in the country, and they are all pretty good at

it.